SESSION MEMORIES & PHOTOGRAPHS BY LEWIS FOREMAN

This release took the Dutton Epoch recording team around the country to four gloriously sounding halls – from Watford to Manchester to Glasgow.

Longest in the can has been Arthur Sullivan’s theatre music for Shakespeare’s Macbeth and The Tempest, with dramatic recitation by Simon Callow and vocal numbers by sopranos Mary Bevan and Fflur Wyn accompanied by the BBC Singers. Also included is the first complete recording of the Marmion Overture (1867). A fine work from Sullivan’s early maturity, its neglect is hard to explain.

Issued as an attractively priced 2-CD set, these recordings feature the BBC Concert Orchestra at Watford Colosseum (Town Hall) and were made during sessions that took place on 3-4 February and 10-11 March 2015. They were also my first sessions with conductor John Andrews, and he knows this composer’s music intimately. I had not encountered soprano Mary Bevan before, and the way her voice soared over the orchestra was enchanting – something I think will thrill all Sullivan devotees.

Simon Callow’s sessions with the Concert Orchestra were superb too, in which he gave renditions of familiar speeches, changing from the witches to Banquo and Macbeth via a range of Scottish accents. Those of the first violins close to him were riveted by his presentation. During the tea breaks, his discussions with John Andrews on points of interpretation found them standing together against the background of a now deserted orchestra.

When Chris Gardner approached Dutton Epoch about recording his father, John Gardner’s Second Symphony (1984-85) with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, there was much head scratching as to what should be the coupling. John Veale’s Second Symphony was my recommendation, and its acceptance satisfied a longstanding ambition to promote a work I thought would appeal to those who relished the more popular of Malcolm Arnold’s symphonies.

During the last twenty years of his life, I regularly visited Veale at his home at Woodeaton, near Oxford, and he loaned me the symphony’s autograph manuscript – but as I had never heard the work my assessment was based entirely on the score. Conductor Martin Yates announced himself keen after reading it, and the sessions, on 3 and 4 June 2015, would be among Dutton Epoch’s last at the RSNO’s old home of Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow. They were remarkably successful, both works a revelation for their character and memorable style. At one point during the Veale, all in the control suddenly shouted, “It’s becoming John Williams!” Written in 1965, the symphony predates any film score it might have reminded us of, and Veale himself was a significant movie composer.

Gardner’s Second Symphony, written more than three decades after his better-known First Symphony, is in a strongly tonal idiom, and the RSNO’s enchanting performance under Martin Yates reveals the Gardner and the Veale as an ideal pairing.

Executive producer Mike Dutton (background) and producer Michael Ponder (foreground) in the control room during the John Veale recording

Martin Yates conducts the Royal Scottish National Orchestra in John Veale’s Second Symphony at Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow

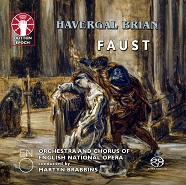

Arriving at Glasgow’s Royal Concert Hall on 5 September 2015 for the Royal Scottish National Orchestra’s recording of Havergal Brian’s Second and Fourteenth symphonies was like opening the door on a magical musical world, for spread out before me were the enormous forces required for the Second Symphony, presided over by Martyn Brabbins, our good-humoured conductor. None of the Second Symphony’s previous performances had employed the huge line-up the score demands – particularly the sixteen horns – but here the detail and grandeur of Brian’s aural canvas was fully recreated.

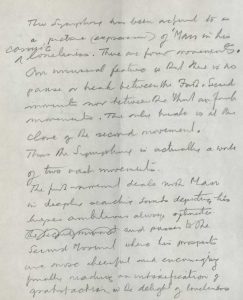

Having been involved in the Second Symphony’s first performance (in 1973), it has always held a special interest for me. I had been able to discuss the music with Brian himself during the year prior to his death. We spoke about which symphony conductor Leslie Head should consider after the success of his premiere in 1969 of Wine of Summer, and Brian’s 95th birthday concert at St. John’s, Smith Square in 1971. Graham Hatton’s preparation of orchestral parts started and went on through much of 1972. We began writing programme notes in the summer of 1972, consulting the composer. He then produced a bombshell in the shape of an utterly new programme for the work, communicated to me in a pencilled note. It was now, “Man in His Cosmic Loneliness”!

The first page of Brian’s pencilled note of July 1972 about the Second Symphony

The recording of the Second and Fourteenth symphonies presented a formidable undertaking (in addition to the huge orchestral line-up, both works also require an organ), the extent of the task evident from the photographs. Not least were the sixteen horns, arranged during the Second Symphony’s scherzo in two equal groups on either side of the hall, the regular line-up (of nine players) returning to their customary position for the other movements. During a break, Martyn Brabbins brought the horns together for a group photograph. Lynda Cochrane and Judith Keaney, the pianists, also stopped for a photograph with the conductor. The timpani and percussion were a special group too, stretched across the back of the orchestra where at moments of peak activity there were as many as ten musicians playing simultaneously. Particularly instructive is the view from the organ console, a vantage point from which can be seen the massed forces.

Only occasionally did questions about specific notes cause Martyn Brabbins to examine the score, which illustrates how thoroughly the project had been prepared, with the combined input of the Havergal Brian Society and John Pickard, himself a composer of international standing. To those present it was an unforgettable occasion, and what we now have is the definitive presentation of these two works.

John Pickard takes a serious view of a query on notes

Dutton Epoch’s first visit to the Hallé at their light and airy rehearsal hall – St. Peter’s, Manchester – on 5-7 January 2016 was a delightful occasion: we were here with soloist Sarah-Jane Bradley and conductor Stephen Bell to record English music for viola and orchestra. The first day opened with Benjamin Dale’s familiar Romance for Viola, orchestrated by the composer in 1910 and premiered by Lionel Tertis under the baton of Arthur Nikisch (whose condescension towards the work irritated Tertis considerably). Dale writes for a surprisingly large orchestra to accompany his solo viola, and the tolling opening chords, noble melody and wide-spanning cantilenas exhibit his style at its most lyrical.

Canadian-born composer Ruth Lomon, to a commission from The Rebecca Clarke Society, has orchestrated Rebecca Clarke’s well-known Viola Sonata in authentic style. A concerto is the result, and one bearing comparison with other viola concerti of the post-WWI period.

Clarke prefaces her score with two lines from French poet Alfred de Musset’s La Nuit de Mai (1835) – preparing us for the romantic and emotionally charged atmosphere:

Poète, prends ton luth; le vin de la jeunesse

Fermente cette nuit dans les veines de Dieu.

I translated this as follows (feeling that blood “fermenting” in the poet’s veins sounded rather stilted):

Poet, take your lute; the wine of youth

Courses this night in the veins of God.

Clarke writes in her autobiography of an experience one summer evening as she passed under a large Syringa bush in full bloom:

It was glistening and dripping with raindrops, and the scent that poured from it, mingling with the primitive, almost cosmic, smell of earth after rain, was so potent that suddenly I was shaken by a rapture beyond anything I had ever known. It was allied to sex – though I did not realise that at the time – but purer: a kind of crystallization of the ecstasy found in music, the awe inspired by the stars.

This erotic charge is certainly in Clarke’s music, and Lomon’s orchestration reinforces the composer’s distinctive voice. “Technically, the work is titled as being in three movements though I see it more as a (dominant) slow movement leading into an agitato finale,” comments Sarah-Jane Bradley.

The rest of the programme consisted of two fresh discoveries. Lionel Tertis championed Richard Walthew’s lovely montage of encores, A Mosaic in Ten Pieces (with Dedication). Originally published in 1900 for clarinet and piano, the composer orchestrated it in 1943 as a viola piece for Tertis to play at that year’s Proms. A charming confection, Sarah-Jane Bradley revelled in the piece and her playing of it is the equal of her legendary predecessor.

Contrastingly, Harry Waldo Warner’s large-scale Suite in D minor, Op. 58 is in three movements. (Waldo Warner is a name familiar from old record catalogues but completely forgotten by most music lovers.) Judging from the opus number, we deduced it must be a late work, probably written during WWII.

The manuscript survived in the collection of Lionel Tertis, and after him his pupil Harry Danks. Its publication and recording was a longstanding ambition of the late John White, for many years Professor of Viola and Head of Instrumental Studies at the Royal Academy of Music, who prepared the edition recorded here, but did not live to hear it played. (The viola and piano manuscript is marked up for string orchestra, the orchestral full score now realised by Tim Seddon.) Again, Sarah-Jane Bradley was a persuasive advocate, playing with authority and a beautiful tone, making it easy to forget how difficult much of the music actually is. She pointed to the last page, Molto allegro, and described it as, “a ridiculous race to the finish, and quite extraordinary viola writing.”

Login Status

Login Status