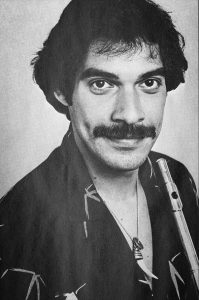

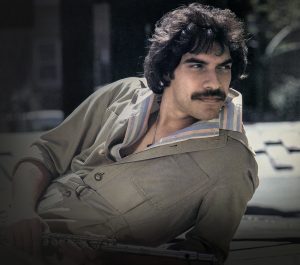

This SACD reissue of flautist Dave Valentin’s fourth album, 1981’s Pied Piper, marks the continuation of Vocalion’s trawl through the vaults of possibly the foremost jazz/MOR label of them all: Arista GRP.

Arista GRP grew out of Grusin/Rosen Productions, which had been set up in 1975 by long-time friends and colleagues Dave Grusin and Larry Rosen who had first met each other in 1960 when Grusin, then working as Andy Williams’s musical director, hired Rosen, a drummer, as part of Williams’s touring band. Their paths would soon diverge, yet Grusin and Rosen reunited in 1973 when Rosen, by now a record producer and recording engineer, hired Grusin to write the orchestrations for singer Jon Lucien’s 1973 album Rashida, which in turn quickly led to the formation of Grusin/Rosen Productions (GRP).

During 1975-77, GRP masterminded albums by violinist Noel Pointer, guitarist Earl Klugh and singer Patti Austin. This period also included Dave Grusin’s fifth solo album, One of a Kind, for the Polydor label. It bore many of the hallmarks that would characterise the next stage in GRP’s evolution: stylish fusion numbers in lush orchestrations, captured in Larry Rosen’s immaculate recordings.

Grusin and Rosen’s work came to the attention of Arista Records’ President Clive Davis, who offered to house Grusin/Rosen Productions under the Arista banner, with all the attendant financial and distribution advantages that would bring, and so in 1978 the Arista GRP label was born, as a wholly owned subsidiary of Arista.

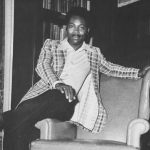

Arista GRP’s initial signing was a young flautist named Dave Valentin. Born in the South Bronx, New York in 1952 to parents of Puerto Rican origin, Dave Valentin studied percussion at New York’s High School of Music and Art before switching to the flute. He progressed so rapidly on the instrument that soon he was supplementing his studies by taking six months of private tuition with renowned flautist Hubert Laws.

Having graduated from the High School of Music and Art, Valentin paid his dues by playing and touring in the Latin bands of pianist Ricardo Marrero and percussionist Manny Oquendo. But, in 1977, Valentin was invited to play on the demo sessions for Noel Pointer’s Grusin/Rosen-produced album Phantazia; suitably impressed, Grusin and Rosen asked Valentin to participate in the upcoming sessions for Grusin’s One of a Kind album, which in turn led to Valentin becoming the first artist signed under the new Arista GRP deal.

Like Valentin’s previous album, 1980’s Land of the Third Eye, Pied Piper featured his touring band in addition to a starry cast of New York session musicians. Numbered among the latter were studio aces such as Marcus Miller (bass guitar), Buddy Williams (drums) and Crusher Bennett (percussion), all of whom had contributed towards creating the distinctive Arista GRP house style.

There’s much to savour here, with Valentin’s by now familiar blend of lush R&B and steamy Latin jazz. The former is represented by the Phyllis St. James-penned title track and Earl Klugh’s lyrical This Time, while Valentin’s touring band is featured to superb effect in the latter material, especially in Seven Stars, a buoyant Dave Valentin composition given wings by the close-knit playing of Tito Marrero, bass guitarist Lincoln Goines and percussionists Roger Squitero and Rafael DeJesus. The standout track, however, is undoubtedly pianist Bill O’Connell’s Dragonfly, a beautiful, almost celestial piece in which a beguiling theme and equally beguiling harmonies draw from both Valentin and O’Connell some truly inspired solos.

This reissue includes a newly written essay detailing Dave Valentin’s career and the history of the Arista GRP label; and, of course, there’s an in-depth discussion of the music itself.

Immaculately recorded by Larry Rosen and suoerbly remastered by Michael J. Dutton from the original stereo master tapes, both albums are presented here for the first time in high-resolution digital stereo, and they sound better than ever before. This Hybrid SACD is fully compatible with all CD players: the SACD layer contains the high-resolution stereo programme, the CD layer the standard 44.1kHz/16-bit CD stereo programme. The SACD layer is playable on any SACD-capable device, while the CD layer provides stereo playback on any standard CD player.

Oliver Lomax

While the passing of the August Bank Holiday may signify the unofficial end of summer in the UK, here at Vocalion we aren’t quite ready to throw in the towel on our own Summer of Quad, and our September slate of titles may be our most exciting group of quadraphonic SACD releases to date. Comprising seven albums across five hybrid quad/stereo discs, the artists that make up this month’s release may all have found common inspiration in jazz, but each followed their respective muses in wildly divergent directions, resulting in albums that run the stylistic gamut from soul, to funk, to jazz-fusion, and even rock and roll.

This month’s release sees Vocalion delving for the first time in to the back catalogue of the mighty Philadelphia International Records – a label as pivotal to the sound and direction of R&B and soul in the ‘70s as Motown was in the ‘60s – for no less than three albums by one of its cornerstones, the inimitable Billy Paul. United on a single disc are Paul’s two finest studio efforts for the label – his 1972 commercial blockbuster, 360 Degrees of Billy Paul, and its 1973 follow-up, the artistically triumphant concept album War of the Gods.

One of Philadelphia’s native sons, Paul exploded in to the public consciousness in the autumn of 1972 with the release of Me and Mrs. Jones, the first single culled from 360 Degrees, but he was far from being a “new” artist. Born in 1934, Paul was nearly 38 by the time the single was released, and had more than two decades of experience as a jazz singer, having made his professional debut by the time he was 16. The album also wasn’t his first outing with PIR principals Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff either – after first crossing paths with the duo in 1968 he released Feelin’ Good at the Cadillac Club (a studio record that replicated his live set) on their Gamble label, followed by Ebony Woman on their Neptune label, before his 1971 album, Goin’ East became PIR’s inaugural release. With each album, Gamble and Huff brought Paul further in to the R&B mainstream (while still being sensitive to his jazz roots) and with the release of 360 Degrees in 1972, everything fell in to place.

Recorded at Philadelphia’s legendary Sigma Sound Studios with PIR’s vaunted MFSB house band, the album overflows with the tight playing and smooth-as-silk string and horn arrangements that would become hallmarks for the label. Paul’s unique vocal style (along with the charisma and gravitas born from his life experience) also helps unite a diverse collection of songs, from the previously mentioned Me and Mrs. Jones (a slow-burning ode to marital infidelity that would go on to sell two million copies and win Paul a Grammy) to Gamble & Huff social consciousness groovers like I’m Just a Prisoner, Am I Black Enough For You and Brown Baby to soul-injected covers of Carole King’s It’s Too Late and Elton John’s Your Song.

Determined not to have Paul repeat the same formula employed on 360 Degrees to diminishing returns, Gamble and Huff went in an entirely different direction when they crafted his follow-up. As much an artistic statement as a musical one, 1973’s War of the Gods found Paul cast almost as a prophet, ruminating on a variety of existential and social topics including war and peace, life and death, and heaven and hell. In many ways the album was PIR’s answer to concept albums like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On and Norman Whitfield’s extended-length forays with the Temptations like Papa Was a Rolling Stone, especially on the mini-suite comprised of I See the Light and War of the Gods, which originally formed the entirety of the album’s first side. Paul doesn’t forget his pop roots on the flipside however, with the one-two punch of the wistful I Was Married and the jubilant Thanks for Saving My Life, the latter giving Paul another top-10 R&B hit. The best, however, is truly saved for last, with the album-closing Peace Holy Peace, a stunning, gospel-infused track that finds Paul delivering a prayer for peace backed by the 22-voice Dandridge Choral Ensemble.

1973 would prove to be a banner year for PIR, with many of its acts (including Paul, The O’Jays, and Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes) enjoying chart-topping success. In December of that year, the label mounted a month-long package tour of Europe that featured Paul, along with label-mates The Intruders and The O’Jays, backed by the MFSB band. Gigs at the Hammersmith Odeon in London and Central Hall in Chatham were recorded, and highlights from those two jubilant shows comprise 1974’s Live in Europe. Featuring repertoire drawn exclusively from 360 Degrees and War of the Gods, the recordings find Paul stretching out on extended versions of some of his most well-known tracks including Me and Mrs. Jones, Brown Baby and Your Song in front of enthusiastic crowds, and displaying all of the charisma and showmanship that helped propel him to the top of the charts that year.

September also sees the continuation of our exploration of the quadraphonic output of Creed Taylor’s CTI Records. In the spotlight this month is George Benson’s 1973 release, Body Talk, an album that finds him deep in the midst of his reputation-making run for the label. Unquestionably one of the finest jazz guitarists to ever pick up the instrument, Benson was a child prodigy, and by his late teens his combination of taste and technique (both as part of Brother Jack McDuff’s quartet and on early solo outings) had begun to mark him as heir apparent to the great Wes Montgomery. That status was only furthered when Montgomery died of a heart attack in 1968 and his label, A&M, signed Benson and paired him with Taylor, who’d helmed Montgomery’s final (and most commercially successful) recordings. Under Taylor’s supervision, Benson would quickly establish himself as a star in his own right, beginning with 1969’s The Shape of Things to Come. Benson would continue to record at a prolific pace with Taylor, also issuing Tell It Like It Is in 1969 and The Other Side of Abbey Road in 1970, but it was Taylor’s decision to take his CTI label (which had been an A&M subsidiary up until that point) fully independent at the end of that year that would usher in Benson’s greatest successes.

In the wake of the split with A&M, Taylor began to record Benson in smaller ensemble settings that put the spotlight more squarely on his endlessly-inventive playing, and the move paid dividends immediately – 1971’s Beyond the Blue Horizon reached No. 15 in the jazz charts, and 1972’s White Rabbit did even better, reaching No. 7. The success of White Rabbit (with its attendant promotional and touring commitments) was such that it was nearly 18 months before Benson and Taylor could reconvene to record what would become Body Talk. Taylor, who seemed to have an uncanny grasp of which way the wind was blowing commercially, set the tone for the album by bringing in saxman and arranger Pee Wee Ellis, who’d been a pivotal member of James Brown’s late-‘60s lineup, arranging and co-writing hits for the Godfather of Soul that included Cold Sweat and Mother Popcorn. Also joining the sessions were CTI stalwarts Ron Carter and Jack DeJohnette, and balancing out the album’s R&B inclinations, hard-bop electric pianist Harold Mabern.

Body Talk also marked the first full-album contribution from Benson’s guitar protégé, 19-year old Earl Klugh, who’d appeared briefly on White Rabbit. Genre mixing always carries the potential for catastrophic failure, but Body Talk more than answers the bell, thanks both to the pedigree of the assembled talent and Benson’s wilfulness as a leader. From the album opener, Dance (which sparkles with the same rhythmic intensity as Ellis’s work with James Brown) to the Latin-influenced title track, to the moody, slow-burning epic Top of the World, Body Talk proves itself to be a well-forged alloy of the rhythmic inventiveness of R&B and funk and the improvisational excitement of jazz.

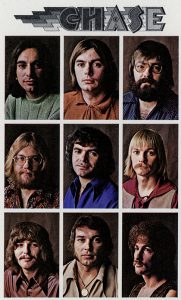

This month also sees two of the quad albums we’ve received the most requests to reissue coming together, with the release of jazz-rock brass powerhouse Chase’s 1971 self-titled debut album, Chase, and 1974 swansong, Pure Music, on a single disc. In the wake of the platinum-selling successes in 1969 and 1970 of bands that combined rock and roll instrumentation with jazz-influenced horn sections like Blood, Sweat & Tears and Chicago, major labels were eager to find the next “big thing” in the same mould. Signing with Epic in late 1970, Chase certainly benefitted from horn-rock gold rush, they weren’t simply a Johnny-come-lately cash-in – they were a breed apart, both in terms of pedigree and also instrumentation, featuring a one of a kind, four-trumpet horn section.

While many jazz-rock bands of the early 70s were really rock and rollers who’d had a little experience in high school jazz band, Chase was the real deal – the brainchild of leader and driving force Bill Chase, a Berklee-educated trumpet virtuoso with a remarkable four-octave range. Beginning in 1958, Chase began to make a name for himself in the big bands of Maynard Ferguson, Stan Kenton, and finally in Woody Herman’s New Herd, where he spent more than half a decade as the outfit’s first chair trumpeter, also writing and arranging for the band. Tiring of the road, in 1966, Chase left Herman’s band and settled in Las Vegas, where he worked the “making the bread circuit” (as Herman called it) playing in various musicals and backing entertainers who played in the city. But by 1968 he’d grown creatively restless, and at the suggestion of his old boss, Herman (one of the first of the jazz “old guard” to embrace rock music), Chase began to work on original music, and in the summer of 1970 the band bearing his name played a three-week residency at Las Vegas’s Pussycat a’ Go Go club that led to a contract with Epic records.

For their 1971 debut album, the label paired the group with producers Bob Destocki and Frank Rand, the same duo who’d helmed the brass-driven #2 smash hit Vehicle for The Ides of March the previous year. The move proved to be a wise one when the album’s first single, Get It On, powered by lead vocalist Terry Richards’ gritty blue-eyed soul vocals and an instant classic horn riff, leapt up the charts and pushed the LP in to the US Top 40. The hit single is far from being the album’s only attraction however, with songs like the instrumental whirlwind Open Up Wide, a gospel-infused cover of Handbags and Gladrags and the jazzy, 14-minute album closing Invitation to a River all showcasing the group’s unique cascading four-trumpet sound, not to mention the instrumental virtuosity of its individual members. Unfortunately for Bill Chase, the success of the band’s first album was followed by the dreaded sophomore jinx when their second album, 1972’s complex and overly serious Ennea, fell flat with critics and fans who were expecting more of the free-wheeling excitement of Get It On. The album’s failure would fracture the original band’s lineup, and Chase’s personal problems were only compounded when he was forced to disband the group and declare personal bankruptcy.

However, he regrouped quickly, and by the end of 1972 he’d put together a new band and had begun working on new material. Over the course of the next 18 months the reconstituted Chase toured relentlessly – during this fallow period Chase experimented with a variety of band configurations, including trying out a sax/flute player, percussionist, and vibraphonist, but by the end of 1973 he’d returned to his signature four-trumpet sound. When the group’s third album, Pure Music, was released in March 1974, it revealed not only a new lineup but also a new sound. If Chase had been something of a jazz-fusion band ahead of its time in its earliest years, with the fusion movement in full bloom by 1974 it had found its moment on Pure Music, fully embracing the genre’s focus on funky rhythms and instrumental improvisation.

With only two of the album’s tracks featuring vocals (courtesy of the Ides of March’s Jim Peterik) the remainder of the album finds Chase and his band stretching out across four epic instrumentals, including the jazzy Weird Song #1, the hauntingly atmospheric Twinkles, and Bochawa, a song with a horn riff that builds in power like a tidal wave. Tragically, however, Chase’s comeback would come to an abrupt end less than six months after the release of Pure Music – en route to a gig, the light aircraft he was travelling in crashed, killing him along with three other members of his band. In the years since, his death has sometimes been reduced to the status of “rock and roll factoid”, but one listen to this pair of superb albums reveals just how vital and alive his music remains, even four decades after the fact.

And finally, rounding things out this month is another hidden gem from the extensive back catalogue of Vocalion fusion favourites Weather Report, 1975’s Tale Spinnin’. It’s often been said that with the warp-speed pace of the group’s musical evolution, and the nearly 30 different musicians that played alongside band principals Wayne Shorter (sax) and Joe Zawinul (keyboards) during the course of its 15 year lifespan, every album was a transitional album. For any fan of the group, it’s an axiom that rings very true, but perhaps never more so than on Tale Spinnin’. Following two critically-acclaimed avant-garde albums in 1971 and 1972 that were primarily acoustic, the group made a concerted turn toward electrified jazz-funk with 1973’s Sweetnighter. The move toward groove was a canny one commercially – Sweetnighter landed the group near the top of the jazz charts in addition to giving them their first appearances on both the pop and R&B charts, but it was at a cost: co-founding bassist Miroslav Vitouš would exit the group after a heated debate with Joe Zawinul over the band’s future direction following the album’s release.

If dabbling with funkier rhythms on Sweetnighter had been something of an experiment, with the recruitment of electric bassist Alphonso Johnson for 1974’s Mysterious Traveller, the band embraced their new identity completely. The album represented a quantum leap in the group’s sound in almost every regard, from its muscular grooves, to Zawinul’s extensive use of cutting edge synthesizer techonology, to an increased reliance on overdubbing, creating songs that were equal parts improvisation and orchestration. Reaching No. 2 in the jazz charts, Mysterious Traveller would be the breakthrough album in Weather Report’s crossover ascendancy when it made it all the way to No. 31 in the R&B Albums chart and No. 46 in the pop charts – no small feat for a record of challenging instrumental jazz. As successful as the album was, the group’s enhanced focus on rhythm took a toll on its percussionists, and when the Mysterious Traveller tour finished, drummers Ishmael Wilburn and Darryl Brown (who’d been brought in to buttress Brown mid-tour) along with long-time percussionist Dom Um Romão all departed the band, leaving it entirely drummerless at the close of 1974.

With an album due to Columbia, Johnson, Shorter and Zawinul regrouped in Los Angeles in early 1975 with legendary engineer/producer Bruce Botnick, known for his long association with both The Doors and Arthur Lee’s Love. Joining the trio were Brazilian percussionist Alyrio Lima and Philadelphian drummer Chuck Bazemore, but early rehearsals quickly revealed that Bazemore’s style didn’t mesh with the band’s sound, and he parted ways with the group. What could have been a difficult situation was resolved in a twist of serendipity – leaving the studio one day after Bazemore’s departure, the group ran in to Santana drummer Leon “Ndugu” Chancler, who had been playing on a session for Jean Luc Ponty in a nearby studio. Zawinul, who was a fan of Chancler’s work with Santana, asked if he’d come in and do a session with the group, and shortly thereafter Chancler joined Weather Report for a week’s worth of recording that would yield Tale Spinnin’.

Sandwiched as it is, between Mysterious Traveller and 1976’s Black Market (which introduced the world to the talents of fretless bass virtuoso Jaco Pastorius), Tale Spinnin’ is often overshadowed by those twin behemoths – the sort of “misfortune” that only a band with a back catalogue as rich as Weather Report could suffer. But Tale Spinnin’ is much more than just an expressway from Mysterious Traveller to Black Market, it’s an album that stands on its own merits. Songs like The Man in the Green Shirt (a prototypical WR combination of an urbane melody with rhythmic ferocity) and the North Africa-tinged Badia offer a sunny, cosmopolitan antidote to Mysterious Traveller’s dark, foreboding aura, while jams like the funky Between the Thighs and the muscular Freezing Fire mark the end of the group’s extended-length forays before the more concise song forms that begin to take hold on Black Market. Sitting at the crossroads between Weather Report’s two eras, Tale Spinnin’s synthesis of long-form musical exploration and studio wizardry in many ways represents the best of both worlds for the open-minded listener.

All of the albums that make up this release have been meticulously remastered by Michael J. Dutton from the original discrete quadraphonic and stereo master tapes, and they all feature extensive newly-penned liner notes (with the exception of Billy Paul’s Live in Europe, which reproduces the album’s original sleeve notes) that offer history, context and analysis on these superb albums.

Vocalion Hybrid SACDs play in three ways – high-resolution multichannel (quadraphonic), high-resolution stereo and standard 44.1kHz/16bit CD stereo. The SACD layer (which contains both multichannel and stereo programmes) is playable on any SACD-capable device, while the CD layer provides stereo playback on any standard CD player.

David Zimmerman

Toronto, 2018

Login Status

Login Status